How to load 220 film in non-automatic Hasselblad magazines

by Q.G. de Bakker

When Victor Hasselblad introduced the 1600 F camera in 1948, photographic film was available in many

different sizes and formats. George Eastman, - "mr. Kodak", the late-1880's inventor of flexible roll film - at

first identified these different film formats by the camera type they were meant to be used in. The film that

would fit a "Pocket Kodak" camera, for instance, was simply called "Pocket Kodak film".

When new cameras appeared, that took the same size film older cameras did, this simple system very quickly

became unworkable. So in 1913 Eastman Kodak decided to abandon the scheme, and began identifying film formats

using numbers.

A film manufactured in 1900 for the Kodak "Brownie No. 2" camera (a Kodak Verichrome film) was the first to be

assigned the type number "120". Following, among others, Francke & Heidecke's lead, Victor Hasselblad decided

to design his first non-military camera, the 1600 F, to use this "120" film. Over time, the 120 format proved to be very

succesful, very popular. Not in the least because of the success of the Rollei and Hasselblad cameras.

The length of a roll of 120 film (approx. 825 mm / 32.5") will accomodate 13 frames of the square 6x6 cm/2.25"

format comfortably. To allow ample room in between frames, and perhaps to get a less ominous frame count

number too, 6x6 cameras typically expose only 12 frames on a roll of 120 film.

Compared to other, larger, formats commonly in use at the time, the increased number of frames per roll was one

of the advantages the smaller 6x6 cm format offered.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, cameras had been produced to use offcuts of long rolls of 35 mm

cinema film. The advantages of these cameras were obvious to photojournalist. Not only did some of them offer

unusually fast (and sometimes extremely good) lenses, but they were small, and easy to conceal as well. This

allowed the photojournalist to blend into the background, and a whole new chapter in the history of

photojournalism began.

Another advantage of these "miniature" cameras was that the long rolls of 35 mm film also made it possible

to increase the number of frames per load, reducing the time spent changing film. Not that important, perhaps, to

a studio based portrait photographer, but invaluable to a photojournalist.

Among the cameras using larger, and shorter, films, the Rolleiflex cameras in particular had been popular

among press photographers. With growing popularity of these 35 mm cinema films (which were first offered as

photographic film in 1934, were given the format number 135, and were sold in confection sizes producing up

to 36 "miniature format" frames per roll), the 12 frames per roll that Rolleis and Hasselblads produce rapidly looked less

appealing.

In the early 1960s film manufacturers introduced a film twice as long as 120 film,

but still small enough to fit in the many cameras that took 120 film. This film was given the type number

220. The first films availabe in this size were the Kodak Tri-X Pan Professional and the Kodak Ektacolor Professional Film, Type S.

The doubling of the film's length, without increasing its girth, was achieved by removing the protective

backing paper, that runs the full length of 120 film. Instead, 220 film only has short protective

paper strips at both ends of the roll.

The removal of the protective backing paper meant it was no longer possible to control film transport using the "peep hole",

or "visual inspection" method employed by many cameras. Using this method, the numbers printed on the backing paper were viewed

through a window on the back of the camera while winding the film to the next frame. Transport was stopped when the next

number appeared in the window. With visual inspection no longer possible, film transport had to be regulated by the

camera or film back itself.

Hasselblad also used this "peep hole" method in their early, non-automatic magazines, but only to wind the film to the first frame

after loading. When the first frame number appears in the window, the frame counter is set to "1", and the mechanism

inside the back controls correct frame spacing for all following frames.

So to allow use of the new 220 film, Hasselblad had to find another way to set the first frame.

But lining up the first frame, ready for exposure, wasn't the only problem. The mechanism used in film backs

like the ones made by Hasselblad regulate frame spacing making use of the fact that with each full rotation of the

take-up spool, a length of film equal to the diameter of the spool was transported.

The diameter of the take-up spool of course increases with the amount of film that is wrapped around it. So the

number of rotations necessary to transport a fixed length of film gradually decreases. The rate of decrease, however,

is a known entity, which can be (and is) incorporated into the spacing mechanism in the shape of a cam or gear, regulating

the successive numbers of rotations of the take-up spool.

The increase in take-up spool diameter of course changes when, instead of the 120's film plus backing paper combination, only

a thin film is wrapped around the take up spool. To ensure correct and even frame spacing with the thinner 220 film, the regulating

mechanism had to be adjusted.

A Hasselblad 220 film magazine that solved both problems was introduced not before 1967. Meanwhile, photographers

who wanted to use 220 film in their Hasselblad film magazines were offered help.

A rubber plug was offered to

seal the peep-hole on the back of Hasselblad magazines, making them light-tight. And instructions how to load 220 film

in Hasselblad magazines were published.

At the time, the Hasselblad "12" film magazine's mechanism already had seen

(at least) two revisions. To ensure best frame spacing with all three variations, Hasselblad published separate

instructions, providing the serial numbers ranges by which to identify each variation.

Hasselblad's original 1965 instructions:

The new 220 film has no protective backing paper and,  therefore, no light must be allowed to leak in through

the film window which must be made light-tight. The manufacturer has therefore made a light-tight plug which

is fitted onto the film window, from inside the magazine, with the number "220" facing outwards. The magazine

can also be sealed against light by affixing black tape across the film window. Like 120 film, the 220 film

has an arrow going across the first paper section. But 220 film has no numbering system. It has, however,

a dotted line, about 6" before the crosswise arrow and this dotted line is very important in connection with

loading this film in the Hasselblad magazine.

therefore, no light must be allowed to leak in through

the film window which must be made light-tight. The manufacturer has therefore made a light-tight plug which

is fitted onto the film window, from inside the magazine, with the number "220" facing outwards. The magazine

can also be sealed against light by affixing black tape across the film window. Like 120 film, the 220 film

has an arrow going across the first paper section. But 220 film has no numbering system. It has, however,

a dotted line, about 6" before the crosswise arrow and this dotted line is very important in connection with

loading this film in the Hasselblad magazine.

To obtain the best possible results in spacing between the negative frames, the manufacturer has prepared

three sets of instructions for the three variations in construction of the Hasselblad Magazine 12 now on the

market.

LOADING INSTRUCTIONS

Magazine Construction 1 (Nos 001 - 19,999)

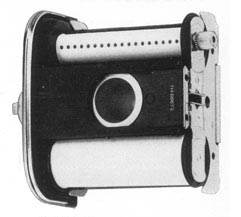

a) Thread the film in the usual manner onto the Hasselblad spool-holder. The protecting paper is drawn

forward so that the dotted line comes to the center of the receiving spool, (see photo).

b) After the spool-holder is inserted in the magazine, set the exposure-counter window at 1.

c) Wind the film forwards 7 complete turns (14 half-turns).

d) Expose 12 frames (no stop).

e) Reset the exposure-counter window to 1.

f) Expose another 12 frames (no stop).

Magazine Construction 2 (Nos. 20,000 - 64,399)

a) Thread the film in the usual manner onto the Hasselblad spool-holder. The protecting paper is drawn

forward so that the dotted line comes to the center of the receiving spool, (see photo).

b) After the spool-holder is inserted in the magazine, set the exposure counter window at 1.

c) Wind the film forwards, 10 complete turns (20 half-turns), or until the framenumber 8 begins to appear

in the mechanism of the exposure-counter window.

d) Reset the exposure-counter window to 1.

e) Expose 12 frames (until stop).

f) Reset the exposure-counter window to 1.

g) Expose another 12 frames (until stop).

Magazine Construction 3 (Nos. 64,400 - )

a) Thread the film in the usual manner onto the Hasselblad spool-holder. The protecting paper is drawn

forward so that the dotted line comes to the center of the receiving spool, (see photo).

b) After the spool-holder is inserted in the magazine, set the exposure-counter window at 1.

c) Wind the film forwards 9 complete turns (18 half-turns), or until framenumber 7 appears in the mechanism

of the exposure-counter window.

d) Reset the exposure-counter window to 1.

e) Expose 12 frames (until stop).

f) Reset the exposure-counter window to 1.

g) Expose another 12 frames (until stop).

Loading in accordance with the above gives relatively good spacing results troughout. In the older magazines,

that is Construction 1 and also Construction 2, it must be expected that certain frames, especially in the

film-section 8-12, can overlap by a few millimeters. But spacing is better in the newest magazine,

Construction 3.

Regarding the loading of Magazine 16 and 16S which have manufacturing numbers below 204.200, these should be

loaded in accordance with the instructions according to Magazine Construction 2; from manufacturing number

204.200 and above, according to Magazine Construction 3. In both cases, the resetting of the exposure-counter

window is to be done after 16 exposures have been made.

| Magazine 12:

Magazine Construction 1 Nos. 001-19,999; 2

Nos. 20,000-64,399; 3 Nos. 64,400- |

| Photo and instruction text from "Hasselblad" magazine, 1965, no. 3, p. 21 |

Copyright 2006 - Q.G. de Bakker. All rights reserved.

All material on this site is protected by law. Unauthorized use is prohibited.

- Hasselblad Historical -